I’ve taken

several weeks of hiatus due to finals, Commencement, and moving into my new

post-college life. I have not, however, severed all ties to my projects from

college. Before I begin my job at Cornerstone Research in July, I will be

prepping to take the GRE in order to apply to graduate school in Economics, and

continue working as a Research Assistant for Prof. Bentley MacLeod at Columbia.

Throughout the last few months, I have been working under the supervision of Elliott Ash to write a paper on selection effects in state supreme courts. There have been opposing theories about the effects of judicial salaries on the makeup (and in particular, the quality) of each state’s supreme courts. In short, some argue that higher judicial salaries produce better judges on the high bench, as these salaries should attract the best and most qualified candidates to the court (remembering that for most states, members of the supreme court choose to run for election). Others argue that we actually get worse judges, since this attracts those who may be more interested in the financial incentives (as opposed to those who, could be argued, were on the bench despite the lower salaries due to their passion for public service and the bench).

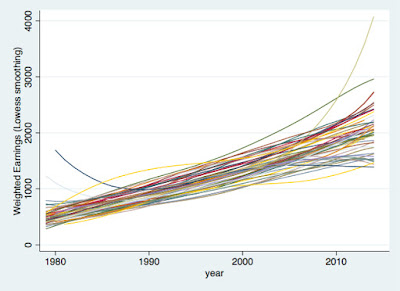

After spending the first several weeks helping other Research Assistants collect data on judicial biographies and elections spanning several decades for all fifty states of the United States, I began constructing a panel data set from NBER extracts of CPS data from the years 1979-2014. This data set would essentially allow us to construct metrics for the average legal industry earnings in each year in each state. These metrics would be used as proxies for “alternative career options” available to those who ran for or served on state supreme courts. After a few weeks of cleaning the data, creating summary variables, and smoothing the resulting measures to arrive at only one observation per year per state (in short, average earnings in the legal industry), the goal has been to use these measures to construct a ratio of judicial to legal industry earnings in each state in each year, in order to run regressions of several measures of judicial quality on this earnings ratio, controlling for several other variables that may affect judicial quality. Thus, these regressions would allow us to answer the original question: does increasing the judicial salary for judges on the state supreme court, relative to alternative career options in the legal industry, give us better or worse supreme court judges, when these judges run for election?

When judicial salaries are more competitive compared to legal industry earnings (meaning the earnings ratio of judicial to lawyer earnings is higher), do we get better or worse judges on the state supreme court? Does a high starting salary ratio guarantee us a higher or lower- quality judge once he’s serving in future years?

Preliminary results showed that we may have insufficient data to determine these effects, so that a further look several years down the line with more available data would be useful. There were also of course a host of other issues that come with the territory of economic research, particularly regarding the standard errors to use and whether to assume or not independence of observations within groups. Throughout the next month or so, I will be working on writing a draft of this paper to consider some of our preliminary results, the current literature, and the issues that have arisen from our regressions and data analysis. I hope to be able to report back sometime in the future with a complete and published paper.

Throughout the last few months, I have been working under the supervision of Elliott Ash to write a paper on selection effects in state supreme courts. There have been opposing theories about the effects of judicial salaries on the makeup (and in particular, the quality) of each state’s supreme courts. In short, some argue that higher judicial salaries produce better judges on the high bench, as these salaries should attract the best and most qualified candidates to the court (remembering that for most states, members of the supreme court choose to run for election). Others argue that we actually get worse judges, since this attracts those who may be more interested in the financial incentives (as opposed to those who, could be argued, were on the bench despite the lower salaries due to their passion for public service and the bench).

After spending the first several weeks helping other Research Assistants collect data on judicial biographies and elections spanning several decades for all fifty states of the United States, I began constructing a panel data set from NBER extracts of CPS data from the years 1979-2014. This data set would essentially allow us to construct metrics for the average legal industry earnings in each year in each state. These metrics would be used as proxies for “alternative career options” available to those who ran for or served on state supreme courts. After a few weeks of cleaning the data, creating summary variables, and smoothing the resulting measures to arrive at only one observation per year per state (in short, average earnings in the legal industry), the goal has been to use these measures to construct a ratio of judicial to legal industry earnings in each state in each year, in order to run regressions of several measures of judicial quality on this earnings ratio, controlling for several other variables that may affect judicial quality. Thus, these regressions would allow us to answer the original question: does increasing the judicial salary for judges on the state supreme court, relative to alternative career options in the legal industry, give us better or worse supreme court judges, when these judges run for election?

When judicial salaries are more competitive compared to legal industry earnings (meaning the earnings ratio of judicial to lawyer earnings is higher), do we get better or worse judges on the state supreme court? Does a high starting salary ratio guarantee us a higher or lower- quality judge once he’s serving in future years?

Preliminary results showed that we may have insufficient data to determine these effects, so that a further look several years down the line with more available data would be useful. There were also of course a host of other issues that come with the territory of economic research, particularly regarding the standard errors to use and whether to assume or not independence of observations within groups. Throughout the next month or so, I will be working on writing a draft of this paper to consider some of our preliminary results, the current literature, and the issues that have arisen from our regressions and data analysis. I hope to be able to report back sometime in the future with a complete and published paper.

A visual summary of the resulting panel data for legal industry earnings, representing average earnings in each state (individual lines) over time from 1979 to 2014. Locally weighted regressions were used to smooth the data to arrive at these results. This data was used to construct a ratio of judicial earnings over legal industry earnings to finally determine the selection effects.

No comments:

Post a Comment