In the empirical research regarding returns from art investments, an

interesting phenomenon has been observed called the masterpiece effect.

Intuitively, if art pieces are indeed believed to be “masterpieces”—or works of

exceptional quality or renown—then we might expect the returns to investing in

these art pieces to uniformly outperform the general portfolio and market.

However, James Pesando, Jianping Mei, and Michael Moses (among others) have

found that masterpieces tend to underperform the market and, in fact, provide

lower cumulative returns than non-masterpieces.

Many economists have contributed their thoughts to explain this

phenomenon. For example, some believe it’s due to overbidding followed by mean

reversion. Thus, masterpieces outperform in one period—we could theorize the

one in which their “masterpiece” status was originated or consolidated—and then

underperform once they’re more established and change hands less frequently

(presumably, these pieces would be coveted and thus not traded as often).

Others suggest that masterpieces are less risky because they’re more

liquid—they may not trade as often, but are definitely easy enough to sell in

the market when they do enter it.

I tend to sympathize with this second theory the most (though the first

also has its merits and, in reality, probably explains some portions of this

effect as well). It is elementary intuition in financial economics that lower

risk involves lower returns. To that extent, non-masterpieces

would provide higher returns because they’re indeed riskier than the

established pieces of art. For these riskier assets, you can buy at a low price

and, with luck, sell at a much higher price later given changing art tastes

(meaning, you’re lucky to buy “speculatively”—buy an emerging or obscure

artist’s work in the hope she will catch on in the art market—and then sell

when your prediction has come true). Yet, of course, this comes at the high

risk that this lesser-known work will not in fact sell, or will not “catch on”.

But, masterpieces should in

theory always be considered eminent, and as such are less risky. Thus, you’d buy at a high price and,

technically, expect to sell at a similarly high price. Their very definition of

masterpieces, after all, means they’re tried and tested works. Because tastes regarding

established works don’t change much (after all, that’s why they’re

“established” parts of the art canon), the only factor affecting increases in

prices for these pieces should be inflation, allowing perhaps for slight changes

in the interest of the artists at a given time (which reduces the investing

game to simply having a sense for when an artist is being paid more attention

to).

Given the above discussion, the

masterpiece effect almost becomes a market efficiency question, in that

masterpieces could be considered assets that trade “efficiently”, while

non-masterpieces may not. Applying the concept of an efficient security to

artwork, because of their very status as masterpieces we can presume we know most

if not all possibly available information about these works and their artists,

so nothing new or material (despite, perhaps, deterioration of the work itself

or discovery as a fake, etc.) should ever come out about that work of art.

Thus, because prices for an asset that trades efficiently should only adjust to

new, material, and public information, we should expect prices for masterpieces

to change very little over time and thus, these works to provide very low (if

not zero) returns.

Because we may lack much more

information on non-masterpieces, and because there is a higher likelihood that

some particular investors or participants in the art market receive more or

better information on them than others (a specification falling more under the

“strong” form of market efficiency as defined by Eugene Fama), non-masterpieces

may thus show inaccurate prices and allow for outsized returns that deviate

from their true value, as compared to masterpieces.

Ashenfelter and Graddy summarize

James Pesando’s discussion of the market efficiency question: when pieces trade efficiently, “the market should

internalize the favorable properties of masterpieces into their prices, so that

risk‑adjusted

returns should not exceed that of other pieces.” Of course, here Pesando

explains the masterpiece effect without relying on the inefficiency of

non-masterpieces. In fact, for Pesando, it is because the market is efficient

for both masterpieces and non-masterpieces that the former do not demonstrate

higher returns than the latter (for non-masterpieces, there's simply more

"new" (presumably good) information about them coming to the market,

so there is more positive price adjustment for newer, non-established works as

opposed to masterpieces). I might claim that the masterpiece effect is observed

perhaps because market efficiency breaks down for non-eminent pieces of art

(again, we can think that assets that are traded very infrequently, that are

paid comparatively little attention, and for which there exists sparse

information, would trade inefficiently compared to those better-known assets,

in the context of the art market).

Of course, this entire discussion relies on some critical questions: firstly, empirical research into this topic requires us to appropriately control for survivorship bias. After all, as mentioned above, masterpieces are presumably much more liquid than non-masterpieces. As such, they are likely to sell much more often so that, when we consider all the non-masterpieces that don’t “survive” in the art market, the cumulative returns of these non-masterpieces may ultimately be below that of the more reliable masterpieces, making the latter ultimately still the better investment.

Of course, this entire discussion relies on some critical questions: firstly, empirical research into this topic requires us to appropriately control for survivorship bias. After all, as mentioned above, masterpieces are presumably much more liquid than non-masterpieces. As such, they are likely to sell much more often so that, when we consider all the non-masterpieces that don’t “survive” in the art market, the cumulative returns of these non-masterpieces may ultimately be below that of the more reliable masterpieces, making the latter ultimately still the better investment.

Secondly and more philosophically (but with much relevance to econometric models), how do we even define masterpieces? The results of any models will ultimately rely on what works are defined as masterpieces, be it through a dummy or other methods.

Lastly, when does an art asset actually trade efficiently? How do we go about showing that an art piece or certain sectors of the art market trade in an efficient way? The “weak” form of efficiency is easy enough to think about: after all, a “weakly” efficient asset is one whose returns cannot be predicted using standard time series methods (in this form, the information set is only past historical prices of the asset). In the "weak" form, asset prices follow a random walk and only respond non-randomly to new information. Stronger forms of efficiency, however, don’t extend as easily to the art market. Conceptually, showing “semi-strong” efficiency would require us proving that prices for these pieces respond as expected to new, material information about these pieces. Yet, an art piece by definition shouldn’t really change much. Thus, there should be very infrequent new information about the piece to move the price. In turn, how would we go about conducting an event study of an art piece’s returns?

This lastly brings us to the most philosophical question of them all: why do prices change so dramatically for artworks at all? Other than inflation, why would a Picasso 50 years from now sell at a much higher price than today? The most obvious answer would simply be changing consumer preferences: perhaps 50 years from now, Picasso is even more popular than he is today. Yet, how do we calculate when the popularity of an artist has changed? How do we define that popularity to then measure and apply to the art market equivalent of an event study? How, at the end of the day, do we know where art prices should adjust—what the true, accurate value of an artwork should be—when art itself can transcend all attempts at understanding?

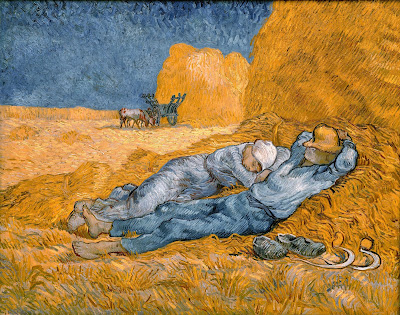

Noon: Rest from Work (after Millet), Vincent van Gogh (1890)

No comments:

Post a Comment